Why we toil

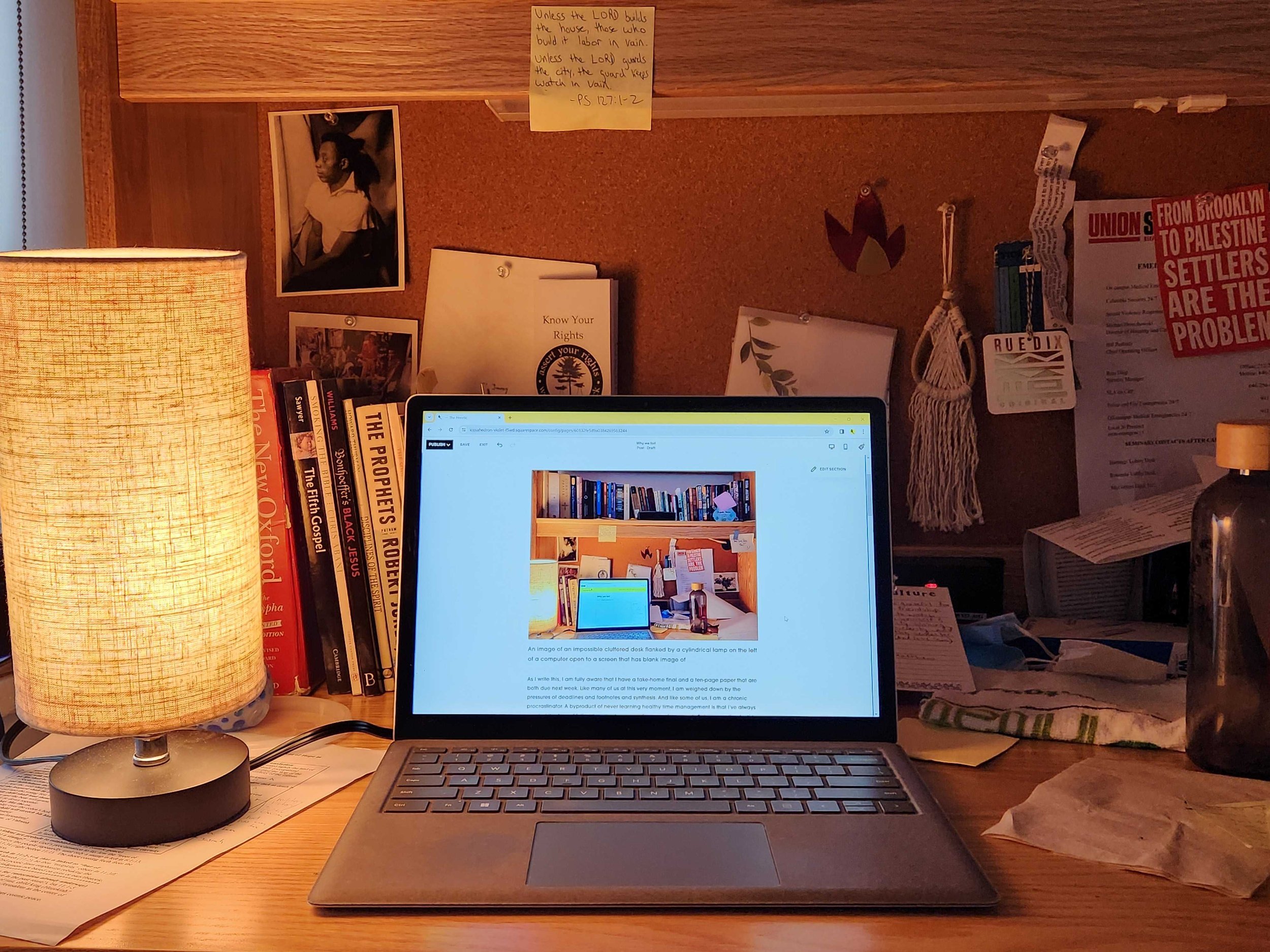

Image description: An photograph of a desk impossibly cluttered by papers, books, napkins, a towel, and a water bottle. (Photo by author)

As I write this, I am fully aware that I have a take-home final and a ten-page paper that are both due next week. Like many of us at this very moment, I am weighed down by the pressures of deadlines and footnotes and synthesis. And like some of us, I am a chronic procrastinator. A byproduct of never learning healthy time management is that I’ve always needed the fear of failure to propel a sense of urgency in my work. But my question for this moment, and perhaps why I’m compelled to put off my academic work to write this, is because I’m afraid that in the busyness of the end of the semester, I have lost the thread on what all of this stress and work are for. To put it simply: Why do we toil?

There's a sticky note above my desk—barely visible thanks to the finals-induced ephemera of clutter surrounding it—with a passage from Psalms 127 scrawled out on it: “Unless the LORD builds the house, those who build it will labor in vain. Unless the LORD guards the city, the guard keeps watch in vain.”

I draw comfort from these verses in the Hebrew Bible because it reminds me that there is ultimately a more powerful, more mysterious force that is required to assemble the world that I profess I am trying to build. It’s truly overwhelming to consider all that I don’t know and have yet to read, in order to productively contribute to a world that centers healing and liberation.

I don’t want to mince words here. I am talking specifically about Black liberation, Palestinian liberation, liberation for all oppressed peoples and species. I was asked recently about what I mean by liberation and how violence fits into it. Shamefully, I cowered in my response because I didn’t know enough, hadn’t read enough, was too privileged to speak on the kind of vision I was allegedly so bent on defending.

We speak so much at Union about having courage. And I am consistently moved by my classmates who do not waver when speaking up and putting their education, reputation, and very bodies on the line in the name of justice and liberation. While I recognize that I have “good words” and have been told as much, I struggle in breaking silence when it matters. After all, there’s good reason to be silent when silence is often needed to get through the day or the dinner without taking on more stress and conflict that it already carries. My heart breaks constantly for the world, for broken relationships in my community, for my own constructed sense of security at the expense of others.

And yet, I toil away at papers and posts and presentations, hoping that on the other side of this willfully elected struggle that the world will be better, my community more healed, my insecurities and anxieties rectified.

Don’t misunderstand me. While I hold true to the idea that liberation comes on the other side of knowing, there is a tremendous amount of wisdom in learning from the ideas of the past so that we don’t have to repeat the same mistakes and also, so that we carry those who toiled for our future long before us with us. So get your work done if it suits you, read your books, and attend your classes while holding to the notion of American theorist Fred Moten: “To the university I’ll steal, and there I’ll steal.” It is precisely a new (stolen) vocabulary that I gleaned from my academic work that approximates the kind of language I hope to manifest in this new world.

And yet, I toil away at papers and posts and presentations, hoping that on the other side of this willfully elected struggle that the world will be better, my community more healed, my insecurities and anxieties rectified.

But I am conflicted at this very moment because I can sense the weariness that the end of the year brings for all of us. And it is not confined to academia.

Religious organizations and nonprofits are scrambling to make quotas for end of year donations just as workers of low-paying jobs are losing sleep to take on extra shifts to meet basic needs on top of paying for the simple joys of giving gifts to loved ones. And all of that matters, just as my ability to submit high-enough-quality work matters. After all, the only way I could afford to live in New York City, or anywhere for that matter, is if I can pay for it through study.

I don’t want to lose the thread here, my original question, what Howard Thurman, the mystic theologian, echoes in his meditation “How Good to Center Down.” He asks: “What are we doing with our lives? What are the motives that order our days? What is the end of our doings? Where are we trying to go? Where do we put the emphasis and where are our values focused? For what end do we make sacrifices?”

The remedy, then, for Thurman, is to be still. To allow the dust to settle so that a “deeper note which only the stillness of the heart makes clear” can ring out in our ears.

It seems simple and highly privileged (and nearly irresponsible) to put everything on hold for a few moments right now. The work will not get done if we don’t do it, but I also think there is wisdom in stillness and silence. I return to the Psalms for both solace and motivation, because for me and for those also shakily clinging to a faith in a loving Creator, it isn’t all up to us.

As we are whisked away out of this season in a flash, I am pained that we have no closing rituals to commemorate the growth and grief that comes with laboring through intellectual and theological work. But my deeper pain is that in fixating on finishing the semester, or submitting the paper, or getting through the day, all of my labor is still in vain. I worry that by training my focus on the accolades that come from doing “good” work that I am actually silencing the stirrings of the kind of work that is required to build a better house in the first place.

So, why do we toil? The Lebanese poet Khalil Gibran writes that “we live only to discover beauty. All else is a form of waiting.”

While I struggle with and challenge the only, I resonate with being drawn to and searching for moments of beauty in the midst of struggle and toil. I’ll admit that beauty is not what comes to mind when I toil. I look for change, affirmation, and confirmation that all of this is worthwhile.

And more often than not, I don’t get to experience it. But if I could speak on the beauty I have found this semester, it would be in the brief moments of passing between places. In the hallways on break, in a chance encounter at a protest, in the affirming glance during chapel, I recall seeing and being seen by my fellow classmates and community members and thinking about how wonderful it is to be on the journey together, to toil alongside one another.

Time and time again, I am brought to the limits of my own “dealing with life,” and time and time again, I discover how much beauty and tenderness exist outside of my own will and production. It’s the tear-soaked shoulders and plates of warm food and doubled-over laughter that makes this waiting bearable. And yes, it’s even in the fruitful, provocative class discussions and Moodle posts that pluck at the cord of heart-clarifying stillness.

I know better than to close my confusion with a benediction. My editors (Kathy and Dayo) already ate me up for my first half-hearted attempt to conclude this neatly. But even the generosity they extended to me in this act of revision is ultimately why I hold on to our impulse to toil.

Seldom is the beauty that I discover in life the product of my attempt to create something worthwhile. Often it is in the midst of struggle when a trusted friend says, “I see you trying to do good and waiting for it to come. All of that waiting and toil is hard. Come sit here for a while and let’s see what we can make together.”